The History of Toyama-ryū Battōdō

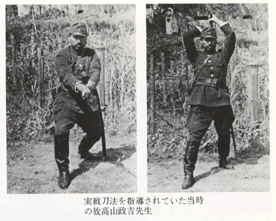

Takayama Masayoshi demonstrates Jissen Budō Takayama-ryū Battōjutsu, the sword method used by the Imperial Japanese Navy, and similar to Toyama Ryū |

The Toyama-ryū Guntō Sōhō (軍刀奏法; military sword methodology) was created and standardized in 1925 by a committee of senior exponents of several sword traditions for the curriculum of the Rikugun Toyama Gakkō (陸軍戸山学校), a military academy of the Imperial Japanese Army founded in 1873. Its conception arose in response to concern that officers would not be able to effectively draw and employ their swords should the need arise while operating in hostile environments. Based on koryū tōhō (古流刀法; classical sword methods), the seven battōhō techniques of the Guntō Sōhō were used to teach army officers how to draw and employ their guntō readily, perhaps particularly in the context of close-quarters trench warfare, which dominated much of World War I.

After World War II ended, the Imperial Japanese Army was disbanded, and the Toyama-ryū Guntō Sōhō survived solely in the hands of a few instructors and former officers. Three of these former officers, one of whom was Nakamura Taizaburo, independently went on teach Toyama Ryū to the public, adapting it to varying degrees for civilian and traditional martial arts pedagogy (adoption of the hakama and keikogi, etc.). Over time, the techniques and interpretations taught by these three instructors began to diverge, but despite an attempt to reconcile the emergent dissimilarities by standardizing their techniques and unifying their teaching organizations, no consensus was reached, and three distinct lines of Toyama Ryū were maintained — the Morinaga style, the Yamaguchi style, and the Nakamura style.

Nakamura Taizaburo, formerly a fencing instructor at the Rikugun Toyama Gakkō, established the Zen Nippon Toyama-ryū Iaidō Renmei (全日本戸山流居合道連盟; All-Japan Toyama-ryū Iaidō Federation) as an organizing body through which to pass down the techniques of Toyama Ryū. Under this organization, an eighth technique, dotangiri (土壇斬り; vertical cut on a target situated upon a mound), was added to the original battōhō curriculum, as well as a six-part kumitachi (組太刀; pre-arranged paired forms) set.

The Establishment of Toyama-ryū Battōdō

At the time that the first open tameshigiri competition was being planned, a more neutral name was solicited so that sword practitioners from other traditions would feel comfortable participating. Additionally, some people felt that the Toyama Ryū name itself invoked memories of the war, and that use of the name outside the now-defunct military was inappropriate. It was at this time that Obata Toshishiro suggested the name battōdō (in lieu of battōjutsu), since iaijutsu had similarly changed to iaidō. Obata's suggestion was adopted by Nakamura's group, who subsequently established the Zen Nippon Battōdō Renmei (全日本抜刀道連盟; All-Japan Battōdō Federation). Several years later, the Zen Nippon Battōdō Renmei splintered into different organizations under the various names of Toyama Ryū, Battōdō, Battōjutsu, Nakamura Ryū, Tōdō, Iai-Battōdō, and others.

Toyama Ryū and Tameshigiri Seminars

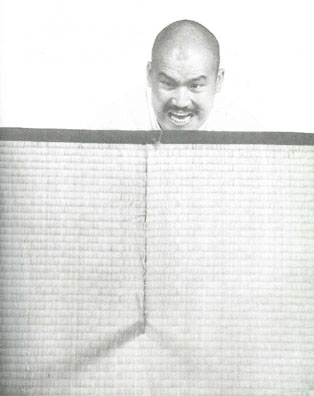

Matomoe-giri: cutting through multiple tatami-omote targets. Photograph published in Naked Blade (Obata Toshishiro, 1986) |

Nakamura-sensei held many seminars in the early years in which Toyama Ryū and tameshigiri were the focus of instruction. However, since the techniques were changing frequently during that time, the instructors who participated in these seminars now remember and teach different forms of Toyama Ryū based on which seminars they had attended.

Many suwari iaidō (practitioners of seiza no bu, or techniques from kneeling) instructors attended these seminars. At one seminar, in which there were 200 participants in attendance, Nakamura-sensei took advantage of the opportunity to ask the iaidō instructors that were present their reasons for wearing the katana and practicing techniques while in the formal seated position (正座; seiza). They invariably replied that they did not know, and that they had been taught this way by their instructors, and in turn taught their own students the same way. None of them had asked their instructors, knew the answer themselves, or had researched the roots of their arts to find out.

The fact is, historically there was no tradition of samurai wearing the katana in the belt while indoors, and while sitting in seiza position in particular, because it violated the samurai code of etiquette. When the long sword is worn indoors, it also creates a disadvantage in regard to freedom of movement. There were several instructors who did not care about the history, and only did what they were taught, regardless of whether it was historically inaccurate or illogical. Unfortunately, there were also instructors present who only cared about receiving high dan rankings, and were there because they were interested in incorporating tameshigiri into their own style. There were probably also people who practiced suwari iaidō or other sword styles that joined Toyama Ryū or Battōdō simply in order to compete in cutting competitions.

Interestingly, though, there were many Toyama Ryū and Battōdō students who cross-trained in other sword arts. One reason may be that there was not enough technique or diversity in Toyama Ryū and Battōdō to be satisfied practicing them exclusively. The eight kata of Toyama Ryū/Battōdō, along with Happōgiri, are too simple and are not sufficient technically for one to properly understand tameshigiri theory and application. The methods must be supplemented with a more comprehensive study of swordsmanship.

Tameshigiri is Not a Sport

Dotangiri through a full tatami floorboard. Photograph published in Naked Blade (Obata Toshishiro, 1986) |

Toyama Ryū was taught at the Toyama army school to officers in order to train them to rapidly deploy their guntō from a draw. As a result, there was not enough basic suburi (sword-swinging) movements in the curriculum, and no kenjutsu-style kata or sparring to supplement the Toyama Ryū training. The officers at that time already had substantial experience in kendō, so adding sparring to their Toyama Ryū training would have been deemed redundant. After the war, however, when the Toyama Ryū federation was first established, Nakamura-sensei created six pre-arranged sparring sequences (similar in flavor to the Kendo no Kata), but which were unrealistic and insufficient when compared to the techniques of koryū kenjutsu. Since there was not enough suburi practice, there were reports of people cutting their knees or palms or evem throwing their swords in the periods before, during, and after World War II. Even Nakamura-sensei writes about his own injuries in his books. Perhaps it is this reason, avoiding injuries, that the movements and sword swings in Toyama-ryū Iaidō have become slow. Originally, Toyama Ryū emphasized speed and strength to allow for it to be used in battle, and this is evident from the photos of officers training in IJA publications.

Since Toyama Ryū has so few techniques in most curriculums, it seems that the emphasis is placed on tameshigiri competitions. If this is the the case, then it must be acknowledged that these lines of Toyama Ryū are no longer being practiced in their original form or with the original spirit. Tameshigiri is necessary to check one's tōhō (刀法; sword methods), but Toyama Ryū must not degrade into a sport focused only on cutting. One must study the fundamentals thoroughly and understand the theory and practice in order to perform proper tameshigiri.

Toyama Ryū Trademark in America

The Toyama Ryū of the Kokusai Toyama Ryū Renmei is taught as gaiden waza in Shinkendo. Since the practice of Toyama Ryū by itself is considered insufficient, as previously stated, it cannot be studied without the practice of Shinkendo. Additionally, since Toyama Ryū® is trademarked in America by the KTRR, any unauthorized use of the name is prohibited.